CONCENTRATION SERVICE

COAGULATION DIAGNOSIS

ANALYZER REAGENTS APPLICATION

BEIJING SUCCEEDER TECHNOLOGY INC.

CONCENTRATION SERVICE COAGULATION DIAGNOSIS

ANALYZER REAGENTS APPLICATION

Acute pulmonary embolism (VTE) is the third most common cardiovascular disease worldwide and the third leading cause of death after myocardial infarction and stroke, posing a serious threat to human health.

The recently released "Guidelines for the Diagnosis and Treatment of Acute Pulmonary Embolism 2025" optimizes and updates the risk factors, diagnostic strategies, risk stratification, anticoagulation, thrombolysis, and interventional treatment options for acute pulmonary embolism, providing a more robust basis for clinical diagnosis and treatment.

The following summarizes the key points.

VTE risk factors are primarily related to venous stasis, endothelial injury, and hypercoagulability (i.e., Virchow's three factors).

These factors can be further divided into intrinsic (mostly permanent) and environmental (mostly temporary) factors, as well as genetic and acquired factors.

Based on odds ratios, these factors can be further categorized as strong, moderate, and weak risk factors. The development of VTE is often the result of a combination of these factors.

Acute pulmonary embolism is caused by a sudden obstruction of the pulmonary artery by a thrombus, triggering varying degrees of pulmonary artery constriction, leading to reduced or even interrupted pulmonary blood flow, and consequently varying degrees of hemodynamic and gas exchange impairment.

In severe cases, this may result in acute myocardial ischemia and necrosis, heart failure, and even death.

Part 1-Optimization of Diagnostic Methods and Strategies

1. Updated D-Dimer Criteria

The specificity of D-dimer for diagnosing acute pulmonary embolism decreases with age.

D-dimer has a high negative predictive value and is primarily used to exclude the diagnosis in hemodynamically stable patients with a low-to-moderate probability of acute pulmonary embolism.

An age-adjusted cutoff value (age × 0.01 mg/L for patients >50 years) is recommended.

This method, while maintaining a sensitivity of 97%, increases specificity to 62% for patients aged 51-60, 50% for patients aged 61-70, 44% for patients 71-80, and 35% for patients aged 80 and over, respectively.

The guidelines recommend that the age-adjusted D-dimer threshold be used instead of the traditional "0.5 mg/L" standard to make the diagnostic criteria more accurate.

2. Refinement of thrombophilia screening

For patients diagnosed with acute pulmonary embolism, if there are:

(1) age < 50 years;

(2) no obvious predisposing factors;

(3) a clear family history of VTE;

(4) recurrent VTE;

(5) VTE in rare sites;

(6) multiple unexplained pathological pregnancies, etc.;

a detailed medical history should be collected, and coagulation indicators (coagulation function, antithrombin activity, protein C activity, protein S activity), immune indicators (antiphospholipid antibodies,

lupus anticoagulants, anti-β2-glycoprotein I antibodies, antinuclear antibody spectrum and other autoantibodies) and thrombophilia gene testing should be completed.

Anticoagulant protein levels may be affected by the acute phase of VTE and/or anticoagulant drugs.

Therefore, it is usually recommended to test at least 2 weeks after the acute phase of thrombosis and after stopping anticoagulant therapy.

If multiple tests consistently show decreased anticoagulant protein levels, the possibility of a hereditary anticoagulant protein deficiency should be considered.

Lupus anticoagulant testing should be performed before anticoagulant therapy or at least one week after discontinuing oral anticoagulants. If the result is positive, the test should be repeated 12 weeks later.

The guidelines emphasize screening individuals suspected of having thrombophilia and specify the population and timeframe for testing functional thrombophilia, which can help identify potential thrombotic factors earlier.

3. Recommended Assessment Models

Based on clinical practice in my country, it is recommended that patients suspected of having acute pulmonary embolism first undergo an assessment of clinical likelihood and pulmonary embolism rule-out criteria, followed by comprehensive laboratory and imaging studies to confirm the diagnosis.

3.1 Clinical Probability Assessment:

Commonly used clinical assessment criteria for acute pulmonary embolism include the Wells score and the Geneva score. The simplified versions of the Wells and Geneva scores are more clinically practical and have been proven to be effective.

In recent years, several new models for the diagnosis and prognosis of acute pulmonary embolism have been developed, of which the "YEARS" model is currently the most widely accepted.

Compared to the Wells score, this model can avoid CTPA in 48% of patients suspected of acute pulmonary embolism.

Guideline Recommendation: For patients clinically suspected of pulmonary embolism, including those during pregnancy or postpartum, the "YEARS" model is recommended as a primary evaluation method to reduce overuse of CT pulmonary angiography (CTPA) and minimize unnecessary radiation exposure.

Evaluation of Low-Probability Patients: For patients with a low clinical probability of acute pulmonary embolism, it is recommended to first assess patients for pulmonary embolism rule-out criteria to improve diagnostic efficiency.

Test Options for High-Risk Patients: For patients suspected of high-risk acute pulmonary embolism, bedside echocardiography or emergency CTPA can be considered to assist in diagnosis, depending on clinical circumstances, to rapidly clarify the condition.

3.2 Assessment of pulmonary embolism exclusion criteria:

If the patient meets all of the following 8 pulmonary embolism exclusion criteria, pulmonary embolism screening is not required:

(1) age <50 years;

(2) pulse <100 beats/min;

(3) blood oxygen saturation >94%;

(4) no unilateral lower limb swelling;

(5) no hemoptysis symptoms;

(6) no recent history of trauma or surgery;

(7) no history of VTE;

(8) no history of oral hormone use.

Guideline recommendations:

For patients with low clinical probability of suspected non-high-risk acute pulmonary embolism, it is recommended to use high-sensitivity or medium-sensitivity methods to detect blood D-dimer levels (I, A).

For patients with high clinical probability of suspected non-high-risk acute pulmonary embolism, CTPA is recommended to confirm the diagnosis (I, B); if there are contraindications to CTPA, pulmonary V/Q imaging can be considered as an alternative examination (II, B).

It is recommended that patients with hemodynamically stable suspected acute pulmonary embolism follow the standard pulmonary embolism diagnostic process (I, B).

Right Ventricular Function Assessment in Select Patients:

For patients with a low Pulmonary Embolism Severity Index (PESI) score or a simplified Pulmonary Embolism Severity Index (sPESI) score of 0, imaging or laboratory testing is recommended to assess right ventricular function and inform subsequent treatment.

All patients with acute PE should undergo a risk stratification assessment to predict the risk of early mortality, including in-hospital mortality and mortality within 30 days.

If a patient presents with hemodynamic instability, they are immediately classified as high-risk.

Hemodynamically stable patients require further evaluation. When the Pulmonary Embolism Severity Index (PESI) reaches grade III-IV or its simplified version (sPESI) score is ≥1, the patient is classified as intermediate-risk.

For intermediate-risk patients, troponin levels should be measured:

if both right ventricular dysfunction and a positive troponin level are present, the patient is classified as intermediate-high risk;

otherwise, the patient is classified as intermediate-low risk. Hemodynamically stable patients with a PESI of grade I–II or an sPESI score of 0 and no right ventricular dysfunction are classified as low risk.

Guidelines recommend:

Initial risk assessment of patients with suspected or confirmed acute PE based on hemodynamic status to identify patients at high risk of early mortality (I, B).

It is recommended that hemodynamically stable patients with acute PE be categorized as intermediate-risk or low-risk (I, B).

The PESI or sPESI score is recommended as a tool for assessing the severity and comorbidities of PE in hemodynamically stable patients (IIa, B).

For patients with acute PE, even if their PESI score is low or their sPESI score is 0, consideration should be given to assessing right ventricular function using imaging and/or biomarkers (IIa, B).

Part 2-New recommendations for anticoagulant therapy

Anticoagulation is the cornerstone of VTE treatment.

For all patients with confirmed or highly suspected acute pulmonary embolism, anticoagulant therapy should be initiated as soon as possible if there are no contraindications to anticoagulation. Contraindications to anticoagulant therapy include:

(1) patients allergic to anticoagulants;

(2) patients with active bleeding;

(3) patients with severe coagulation abnormalities;

(4) patients with bleeding disorders, including hemophilia and thrombotic thrombocytopenic purpura;

(5) other contraindications related to the pharmacological properties of different anticoagulants.

Timely anticoagulant therapy is the key to reducing in-hospital mortality and preventing VTE recurrence.

Currently used anticoagulants are mainly divided into parenteral anticoagulants and oral anticoagulants.

1. Parenteral anticoagulants

Unfractionated heparin:

When using unfractionated heparin for anticoagulant therapy, it is necessary to monitor the activated partial thromboplastin time (APTT) and adjust the dose according to the APTT.

During the first 24 hours, monitor the APTT every 4–6 hours to ensure that the APTT reaches and maintains 1.5–2.5 times the normal value within 24 hours.

Once stable, monitor the APTT daily. Heparin-induced thrombocytopenia may occur during heparin use.

If a decrease in platelet count is observed, increase monitoring frequency to 1–2 times daily.

Once thrombocytopenia is confirmed or highly suspected, heparin should be discontinued immediately and switched to a non-heparin anticoagulant, such as bivalirudin, argatroban, or fondaparinux. Subsequent maintenance therapy often uses warfarin as an alternative.

Low-molecular-weight heparin:

Low-molecular-weight heparin is the preferred parenteral anticoagulant for acute pulmonary embolism, with a lower risk of major bleeding and thrombocytopenia than unfractionated heparin.

Low-molecular-weight heparin should be administered subcutaneously 1–2 times daily, based on weight.

Routine monitoring is not required during treatment with low-molecular-weight heparin.

However, for elderly patients or those with renal impairment, the dose should be reduced and monitoring of anti-factor Xa activity is recommended for dose adjustment.

The target range for anti-factor Xa activity for twice-daily dosing is 0.6-1.0 U/mL.

Low-molecular-weight heparin is contraindicated in patients with severe renal impairment (creatinine clearance <15 mL/min).

Platelet count monitoring is necessary when low-molecular-weight heparin treatment lasts longer than 7 days.

Fondaparinux:

Fondaparinux is a selective factor Xa inhibitor that is administered subcutaneously once daily, based on weight. Routine monitoring is generally not required.

The dose should be halved in patients with moderate renal impairment (creatinine clearance 30-59 mL/min) and is contraindicated in patients with severe renal impairment (creatinine clearance <30 mL/min).

Argatroban:

It is a direct thrombin inhibitor. It exerts its anticoagulant effect by binding to the active site of thrombin and is indicated for patients with thrombocytopenia or suspected thrombocytopenia. It is primarily metabolized in the liver, and its clearance is affected by liver function. The recommended dosage is 2 μg·kg⁻¹·min⁻¹ by intravenous infusion, while monitoring the APTT to ensure it remains between 1.5 and 3.0 times the baseline value.

Bivalirudin:

Bivalirudin exerts its anticoagulant effect by directly and specifically inhibiting thrombin activity and is indicated for patients with thrombocytopenia or suspected thrombocytopenia.

The recommended starting dose is 0.15-0.2 mg·kg⁻¹·h⁻¹ by intravenous infusion, maintaining the APTT between 1.5 and 2.5 times the baseline value. Patients with renal insufficiency require a reduced dose.

2. Oral anticoagulants

After initiating initial parenteral anticoagulant therapy, oral anticoagulants should be promptly switched to according to clinical conditions. Commonly used oral anticoagulants are divided into vitamin K antagonists and direct oral anticoagulants (DOACs).

(1) Vitamin K antagonists:

The most commonly used is warfarin. The recommended initial dose of warfarin is 2.5 to 3.0 mg once daily.

For the elderly, women, patients with liver and kidney dysfunction, chronic heart failure, or patients with a high risk of bleeding according to the HAS-BLED score, the initial dose can be started at 1.25 to 1.5 mg.

When using warfarin, it is usually necessary to overlap with parenteral anticoagulants for more than 5 days and monitor whether the international normalized ratio (INR) of the prothrombin time reaches the target range (2.0 to 3.0).

After the INR reaches the target, it can be tested once every 1 to 2 weeks, and once it stabilizes, it can be tested once every 4 to 12 weeks.

When the INR value is greater than 3.0, warfarin should be discontinued immediately.

The discontinuation time and intervention measures should be determined based on the INR level and bleeding risk.

Specifically, when the INR is 3.0<~4.5 and there is no bleeding or bleeding tendency, discontinue the drug for 1~3 days.

After the INR is 2.0~3.0, resume warfarin at a dose reduced by 1/4 compared to before discontinuation.

When the INR is 4.5<~10 and there is no bleeding or bleeding tendency, discontinue the drug and recheck the INR every 1~3 days until the INR drops to 2.0~3.0.

Restart warfarin at a dose reduced by 1/2 compared to before discontinuation. Recheck the INR within 5 days of resuming warfarin treatment and adjust it again according to the result until the INR stabilizes at 2.0~3.0.

When the INR is greater than 10 and there are no signs of bleeding, in addition to discontinuation of the drug, oral or intramuscular vitamin K can be used.

When a bleeding event occurs, vitamin K can be immediately injected slowly intravenously (10 mg/time), and can be combined with prothrombin complex or fresh frozen plasma to quickly reverse anticoagulation.

(2) DOACs:

DOACs are a class of anticoagulants that directly inhibit thrombin or coagulation factors, mainly including direct factor Xa inhibitors (such as rivaroxaban, edoxaban and apixaban) and direct factor IIa inhibitors (such as dabigatran etexilate).

Multiple clinical trials have shown that DOACs are not inferior to standard treatment with low molecular weight heparin bridged to warfarin in terms of efficacy, and the incidence of major bleeding is lower or no difference.

DOACs have the advantages of fixed dose administration, no need for routine monitoring, few interactions with food and drugs, definite efficacy and higher safety.

Rivaroxaban and apixaban can be used as monotherapy for initial treatment without the need for combined parenteral anticoagulants.

A loading dose is required in the initial stage of use.

When dabigatran etexilate and edoxaban are used, parenteral anticoagulants must be given for at least 5 days.

For patients with moderate-risk pulmonary embolism, early switching from parenteral anticoagulation to dabigatran etexilate (within 72 hours) is recommended.

If bleeding occurs while taking DOACs, the drug should be discontinued immediately.

Antagonists or inhibitors, such as the dabigatran-specific antagonist idarucizumab and the direct factor Xa inhibitor andraconazole, may be used as appropriate. Prothrombin complex concentrate or fresh frozen plasma may also be considered.

The novel factor Xa inhibitor Milvexian has been shown to be effective and safe for preventing VTE after total knee arthroplasty and may also be used in the future for the treatment of acute pulmonary embolism.

Guideline Recommendations:

Immediate initiation of parenteral anticoagulation is recommended for patients with a high suspicion of acute pulmonary embolism (I, C).

Once acute pulmonary embolism is confirmed, anticoagulation therapy is recommended as soon as possible if the patient has no contraindications to anticoagulation (I, C).

Oral anticoagulation with DOACs is recommended as the preferred treatment for acute pulmonary embolism (I, A).

If warfarin is chosen for anticoagulation therapy of acute pulmonary embolism, it is recommended that warfarin be administered concurrently within 24 hours of initiating parenteral anticoagulation and that the INR be adjusted to 2.0-3.0. Parenteral anticoagulation can be discontinued once the INR reaches the target (I, A).

Duration of anticoagulation therapy:

Anticoagulation therapy for acute pulmonary embolism should be administered for at least 3 months.

Extended anticoagulation therapy can reduce the risk of VTE recurrence during treatment but does not reduce the risk of VTE recurrence after discontinuation of anticoagulation.

It may also increase the risk of bleeding.

Therefore, the risk of VTE recurrence and bleeding should be carefully weighed to select patients suitable for extended or long-term anticoagulation therapy.

Long-term anticoagulation is generally indicated for patients with inherited thrombophilias, persistent risk factors, recurrent VTE, or active cancer.

Guideline Recommendations:

Anticoagulation therapy for at least 3 months is recommended for all patients with acute pulmonary embolism (I, A).

For patients with non-tumor acute pulmonary embolism who have transient or reversible risk factors, a 3-month anticoagulation course is recommended (I, B).

For patients with non-tumor acute pulmonary embolism who have persistent risk factors or no significant risk factors, extended anticoagulation after 3 months is recommended (IIa, C).

For patients with recurrent VTE who do not have transient or reversible risk factors, long-term anticoagulation is recommended (I, B).

For patients with antiphospholipid syndrome, long-term anticoagulation with a vitamin K antagonist is recommended (I, B).

For patients with inherited thrombophilia, long-term anticoagulation is recommended (IIa, B).

Part 3-Thrombolysis and Interventional Therapy Guidelines

Systemic Thrombolysis

Thrombolysis is an important measure to rapidly dissolve thrombus, restore lung perfusion in high-risk patients, and reverse right heart failure.

It can help rapidly improve hemodynamic instability caused by acute pulmonary embolism and reduce mortality and recurrence rates.

(1) Commonly used thrombolytic drugs:

The first generation of thrombolytic drugs is represented by streptokinase and urokinase.

Streptokinase is not recommended for the treatment of acute pulmonary embolism in clinical practice.

Urokinase can directly act on the endogenous fibrinolytic system.

This guideline recommends: a thrombolytic treatment regimen of urokinase 20,000 U/kg intravenous drip for 2 hours.

The second generation of thrombolytic drugs includes plasminogen activators, recombinant tissue plasminogen activator (rt-PA) and urokinase.

The guideline recommends rt-PA 50-100 mg continuous intravenous drip for 2 hours, and the total dose for patients weighing <65 kg should not exceed 1.5 mg/kg.

The third generation of thrombolytic drugs includes reteplase, tenecteplase and ranteplase.

Among them, reteplase is a long-acting and highly specific thrombolytic drug.

Clinical studies have confirmed that reteplase (18 mg intravenous push for more than 2 minutes, repeated once after half an hour) has a definite short-term efficacy and good safety in the treatment of thrombolytic patients with moderate-risk acute pulmonary embolism.

(2) Thrombolysis time window:

The thrombolysis time window refers to the time from the onset of clinical symptoms caused by thrombus blocking the pulmonary artery or its branches to the start of thrombolysis.

The determination of the time window needs to be combined with the onset time and recurrence time of acute pulmonary embolism.

The shorter the thrombolysis time window, the better, preferably within 48 hours of onset, and the longest should not exceed 2 weeks.

Guidelines for the placement of inferior vena cava filters

For patients with acute pulmonary embolism who have absolute contraindications to anticoagulant therapy, the placement of an inferior vena cava filter can be considered (Ⅱa, C).

For patients with recurrent pulmonary embolism after adequate anticoagulant therapy, the placement of an inferior vena cava filter can be considered (Ⅱa, C).

It is usually not recommended to routinely place an inferior vena cava filter in patients with pulmonary embolism (Ⅲ, A).

Indications for catheter-directed interventional therapy (CDT).

For patients with high-risk acute pulmonary embolism, if there are contraindications to thrombolytic therapy or treatment failure, or for patients with medium- and high-risk acute pulmonary embolism who experience clinical deterioration after anticoagulant therapy and have contraindications to thrombolytic therapy or treatment failure, it is recommended to start CDT.

However, routine CDT is not recommended for patients with acute intermediate-risk or low-risk pulmonary embolism.

Part 4-More Scientific Risk Stratification

Clarifying the correlation between the severity of acute pulmonary embolism and the risk of early mortality will help physicians more accurately assess patient prognosis.

Patients with acute pulmonary embolism should choose treatment strategies based on risk stratification.

Emergency Management of High-Risk Acute PE:

Emergency management of high-risk acute pulmonary embolism includes prompt hemodynamic and respiratory support and early initiation of anticoagulant therapy.

Guidelines recommend early initiation of anticoagulant therapy for patients with high-risk acute pulmonary embolism, with intravenous unfractionated heparin preferred to facilitate rapid subsequent adjustment of treatment plans (I, C).

Systemic thrombolytic therapy is recommended for patients with high-risk acute pulmonary embolism who do not have contraindications to thrombolysis (I, B).

For patients with high-risk acute pulmonary embolism who have contraindications to thrombolysis or who have failed thrombolytic therapy, surgical pulmonary artery thrombectomy may be considered, provided appropriate surgical expertise and conditions are available (IIa, C).

For patients with high-risk acute pulmonary embolism who have contraindications to thrombolysis or who have failed thrombolytic therapy, CDT may be considered (IIa, C).

Patients with high-risk PE may be treated with norepinephrine and/or dobutamine (IIa, C).

For patients with PE associated with refractory circulatory failure or cardiac arrest, ECMO combined with surgical pulmonary embolectomy or CDT may be considered (IIa, C).

Treatment of moderate-risk acute PE:

Patients with moderate-risk acute PE require hospitalization for anticoagulation. Most patients with moderate-risk acute PE require only anticoagulation; routine thrombolysis is not recommended.

Guideline recommendations:

Immediately initiate anticoagulation for moderate-risk acute PE (I, C).

If hemodynamic instability develops during anticoagulation, immediate rescue thrombolysis is recommended (I, B), or surgical pulmonary embolectomy and CDT may be considered (IIa, C).

Routine systemic thrombolysis is not recommended for patients with moderate- or low-risk acute PE (III, B). CDT is not recommended as a routine treatment for patients with intermediate-risk and low-risk acute pulmonary embolism (III, C).

Treatment of low-risk acute pulmonary embolism:

Anticoagulant therapy is recommended for patients with low-risk acute pulmonary embolism.

For low-risk patients who meet the following three criteria, early discharge or outpatient anticoagulant therapy may be considered:

(1) Low risk of death or worsening of pulmonary embolism-related illness;

(2) No serious comorbidities requiring hospitalization;

(3) Appropriate outpatient anticoagulant management can be provided, and patient compliance is good.

Guideline recommendation:

For patients with non-high-risk acute pulmonary embolism, low molecular weight heparin or fondaparinux sodium is the preferred initial parenteral anticoagulant therapy (IA).

It is recommended that patients with stable low-risk pulmonary embolism be discharged as soon as possible and receive anticoagulant therapy at home using DOACs while providing appropriate outpatient anticoagulant management (IIa, A).

Part 5-Special Populations

Diagnosis of Acute Pulmonary Embolism During Pregnancy

A negative D-dimer level in pregnant women can rule out acute pulmonary embolism, but an elevated D-dimer level cannot diagnose pulmonary embolism. For patients suspected of acute pulmonary embolism during pregnancy, the "YEARS" model can be used to safely rule out pulmonary embolism, which can avoid CTPA in 32% to 65% of cases. An electrocardiogram (ECG) and chest radiograph are recommended for suspected patients. Approximately 40% of pregnant women with acute pulmonary embolism have abnormal ECGs. Pulmonary V/Q scintigraphy or CTPA should be performed when suspicion is high.

Treatment of Acute Pulmonary Embolism During Pregnancy

Anticoagulation is the mainstay of treatment for pulmonary embolism during pregnancy. Unfractionated heparin and low molecular weight heparin, both of which do not cross the placenta and do not increase the risk of fetal bleeding or teratogenicity, are the drugs of choice.

The recommended course of anticoagulation for acute pulmonary embolism during pregnancy is 3 to 6 months, continued for at least 6 weeks postpartum. Thrombolytic therapy should be considered for high-risk acute pulmonary embolism during pregnancy.

Guideline recommendations:

The "YEARS" model is recommended for patients with suspected acute PE during pregnancy or the postpartum period to exclude the diagnosis (IIa, B).

Lower extremity venous compression ultrasound is recommended for pregnant patients with a history and symptoms of DVT to assist in the diagnosis of PE (IIa, B).

Pulmonary V/Q scintigraphy or CTPA (low-radiation-dose protocol) should be considered to exclude PE during pregnancy (IIa, C).

Low-dose low-molecular-weight heparin is recommended as the preferred initial and long-term anticoagulant therapy for hemodynamically stable patients with acute PE during pregnancy (I, B).

Thrombolytic therapy may be considered for high-risk patients with acute PE during pregnancy (IIa, C).

DOACs are not recommended for patients with PE during pregnancy (IIa, C).

The incidence of VTE in cancer patients is 4-7 times higher than in non-cancerous patients and is more common in pancreatic cancer, lung cancer, gastrointestinal cancer, and ovarian cancer.

Diagnosis

D-dimer levels are higher in patients with malignant tumors than in healthy controls. Therefore, diagnosing acute pulmonary embolism in cancer patients based on D-dimer levels is not recommended. Imaging methods such as CTPA should be considered first. If the patient has renal insufficiency or is allergic to contrast agents, pulmonary V/Q scintigraphy can confirm the diagnosis.

VTE risk assessment in cancer patients is primarily based on the Caprini scale (preferred for surgical patients) and the Khorana scale (preferred for medical and outpatient patients).

Treatment

For patients with cancer and acute pulmonary embolism, low-molecular-weight heparin is the preferred initial anticoagulation (at least 10 days). Low-molecular-weight heparin or DOACs can be continued after 5-10 days of initial treatment. If there is no high risk of gastrointestinal or genitourinary bleeding, oral rivaroxaban, apixaban, or edoxaban are preferred. For cancer patients with a higher risk of bleeding, low-molecular-weight heparin is preferred. Anticoagulation therapy is recommended for at least 3-6 months. The decision to extend anticoagulation should be based on individual assessment of the benefit-risk ratio, tolerability, drug availability, patient preference, and cancer activity. For patients with active malignancies, if the bleeding risk is not high, extended anticoagulation or even lifelong anticoagulation is recommended.

Guideline Recommendations:

D-dimer testing is not recommended for the diagnosis of acute pulmonary embolism in cancer patients (III, B).

Low molecular weight heparin is recommended as the preferred initial anticoagulation for patients with cancer and acute pulmonary embolism (I, A).

If there is no high risk of gastrointestinal or genitourinary bleeding, apixaban, rivaroxaban, and edoxaban may be preferred (I, A).

For patients with cancer and VTE, at least 6 months of anticoagulation is recommended (I, A).

For patients with uncured malignancies, if the bleeding risk is not high, extended anticoagulation or even lifelong anticoagulation is recommended (IIa, A).

The updated "Guidelines for the Diagnosis and Treatment of Acute Pulmonary Embolism 2025" provides clinicians with more detailed and scientific guidance on the diagnosis, treatment, and management of acute pulmonary embolism, helping to improve the diagnosis and treatment of acute pulmonary embolism and improve patient outcomes.

We encourage all medical professionals to pay attention to the key points of the guideline updates and better serve patients.

References: Guidelines for the diagnosis and treatment of acute pulmonary embolism 2025[J]. Chinese Journal of Cardiology

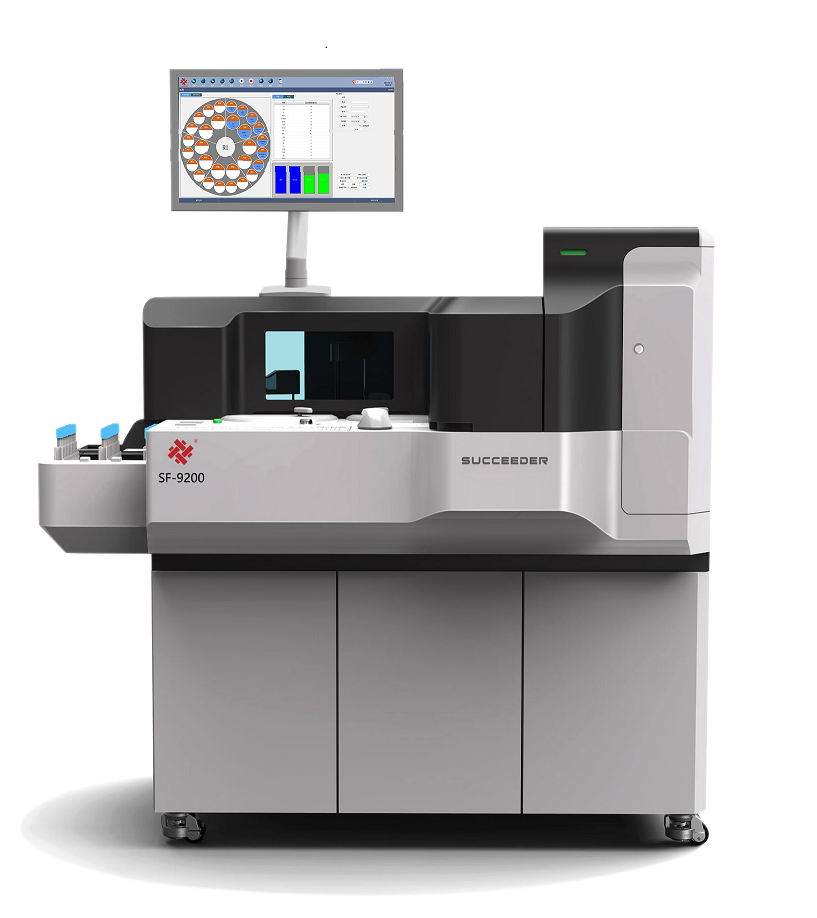

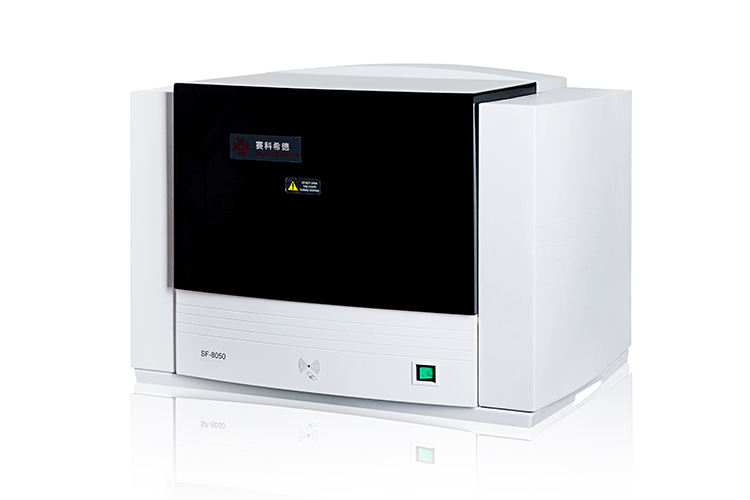

Beijing Succeeder Technology Inc. (stock code: 688338) has been deeply engaged in the field of coagulation diagnosis since its establishment in 2003, and is committed to becoming a leader in this field.

Headquartered in Beijing, the company has a strong R&D, production and sales team, focusing on the innovation and application of thrombosis and hemostasis diagnostic technology.

With its outstanding technical strength, Succeeder has won 45 authorized patents, including 14 invention patents, 16 utility model patents and 15 design patents.

The company also has 32 Class II medical device product registration certificates, 3 Class I filing certificates, and EU CE certification for 14 products, and has passed ISO 13485 quality management system certification to ensure the excellence and stability of product quality.

Succeeder is not only a key enterprise of the Beijing Biomedicine Industry Leapfrog Development Project (G20), but also successfully landed on the Science and Technology Innovation Board in 2020, achieving leapfrog development of the company.

At present, the company has built a nationwide sales network covering hundreds of agents and offices.

Its products are sold well in most parts of the country.

It is also actively expanding overseas markets and continuously improving its international competitiveness.

We keep moving forward

Business card

Business card Chinese WeChat

Chinese WeChat